- Home

- Bernice Yeung

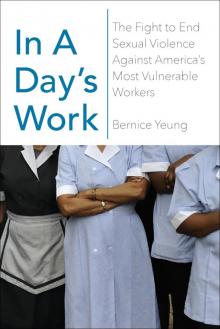

In a Day's Work

In a Day's Work Read online

© 2018 by Bernice Yeung

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Letter on pages 197–199 used by permission of Georgina Hernández.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2018

Distributed by Two Rivers Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-316-5 (e-book)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Yeung, Bernice, author.

Title: In a day’s work: the fight to end sexual violence against America’s most vulnerable workers / Bernice Yeung.

Description: New York: New Press, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017053297

Subjects: LCSH: Sexual harassment—United States. | Women foreign workers—Crimes against—United States. | Women immigrants—Crimes against—United States. | Sexual abuse victims—United States. | Sex crimes—United States. | Violence in the workplace—United States.

Classification: LCC HD6060.5.U5 Y48 2018 | DDC 362.88086/910973—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017053297

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition by dix!

This book was set in Fairfield LH

24681097531

To the women who shared their

stories with us, and to those who couldn’t.

And for my father, who has shown me the

importance of crossing borders.

These places of possibility within ourselves are dark because they are ancient and hidden; they have survived and grown strong through darkness. Within these deep places, each one of us holds an incredible reserve of creativity and power, of unexamined and unrecorded emotion and feeling. The woman’s place of power within each of us is neither white nor surface; it is dark, it is ancient, and it is deep.

—Audre Lorde, from “Poetry Is Not a Luxury”

Contents

Introduction: The Weight of Silence

1. Finding the Most Invisible Cases

2. The Open Secret

3. Behind Closed Doors and Without a Safety Net

4. When Only the Police and the Prosecutor Believe You

5. All That We Already Know

6. The Ways Forward

7. ¡Sí Se Pudo! Yes We Did!

Epilogue: “I survived”

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Introduction

The Weight of Silence

It neared dusk as we drove into the depths of a small community built around farms and fields of the Pacific Northwest. The clouds were low and gray as we navigated a busy two-lane road that led in and out of town, past a Mexican restaurant, a diner, and a farmsupply store.

Just beyond a pizza parlor, we turned off the main road and continued past the length of a parking lot until we found a cluster of one-story brick apartments. In one of them lived a farmworker who we will call Rosa. She was the reason my colleague Grace and I had come to town.

As journalists, Grace and I were on a reporting team working to expose a long-held but open secret: immigrant women in some of the most financially precarious jobs—many of whom are undocumented—were being targeted for sexual abuse by their superiors. We wanted to meet with Rosa because, according to a lawsuit that she and her family had filed, she had been sexually harassed at work. Worse, Rosa’s sister had been repeatedly raped by a supervisor there.

Reading the case file had left me internalizing the weight of their story. The detailed descriptions of the rapes were difficult to get through. She said her supervisor had violated her in a farm shed while he held gardening shears to her throat. He pulled her hair or slapped her while he raped her because he said she wasn’t putting enough effort into it. Then he coerced her into silence by threatening to kill her children in Mexico or by reminding her of the power he had to fire her sister and brother, who also worked at the same farm. The supervisor knew that for workers not authorized to be in the country, the prospect of losing a job was almost as menacing as a death threat.

This case exemplified the phenomenon our reporting team was seeking to uncover: how immigration status and poverty are leveraged against female workers to hold them hostage in jobs where they are being sexually abused. Rosa’s sister seemed too traumatized for us to approach directly, so Grace and I had decided to talk to Rosa first.

We parked the car and made our way into a grassy courtyard in search of the right apartment. We circled the complex and stopped at a door facing the street to check the number against our notes. This was it. We knocked.

The woman who answered had a broad face and high cheekbones. She still wore the jeans and fleece vest that she had put on before starting a shift at an egg production plant nearby. Grace and I introduced ourselves and told Rosa why we were there. She surveyed us warily. When we mentioned the name of the person who’d suggested we contact her, she reluctantly beckoned us inside.

We followed Rosa through the living room, which had been partitioned by curtains to create a third makeshift bedroom, and into the kitchen. Rosa was in the middle of making dinner, resuscitating leftover mole sauce that a friend had given her. As the pot bubbled on the stove, we sat down at the table to get to know one another. Our conversation spanned the mundane to the meaningful: cooking techniques, her children, and her journey from Mexico through the desert to the United States. After a time, she insisted that we share in the meal. She had added chicken to the sauce, which was rich and hearty.

Before the end of the evening, Rosa agreed to speak with us about what had happened to both her and her sister at the farm where they had worked. Like many of the women we encountered, she said she wanted to bring attention to an untenable problem and hoped that by doing so, she would help other women.

But as we talked, a thought occurred to her. Before she agreed to a recorded interview for possible radio and television broadcast, she had some questions. How would taking such a public stance affect her job? More important, what if the supervisor who had raped her sister found out and decided to retaliate against them? She added that she had run into him just the week before at a quinceañera and he’d given her a dirty look. Before that, she had spotted him at the local Walmart.

Grace and I didn’t have any answers for Rosa, and we told her so. In fact, as reporters, we could promise her little except the possibility of protecting her identity and telling her story with fidelity. We suggested that she talk to someone who she trusted about whether she should agree to continue speaking with us or not. About a week later, we got word that despite her altruistic impulses, Rosa had decided not to proceed.

It was easy for us to understand why. On our third and last visit with Rosa, she had taken us into her bedroom, packed with cleaning supplies and beauty products. There, standing next to her bed, she pulled out her phone to show us pictures of her two teenage kids. She had left them with her mother eight years ago when she had come to America in search of work to support them. In the way that her smile widened at their image, it was clear: her kids and her ability to provide for them were the sun around w

hich she revolved.

When Rosa and everyone else in her situation are asked to make it publicly known that they’ve been raped or otherwise sexually assaulted, the stakes for them are impossibly high. The potential collective good is weighed against what is immediately and urgently necessary. Because there is no assurance that speaking out will be met with protection from future or collateral harm, the only rational thing to do is to say nothing. After meeting Rosa, I came to understand why so many sexually abused workers have for so long abided in silence.

Grace and I had gone looking for Rosa in the fall of 2012, but the effort to uncover the stories of women farmworkers who had been sexually abused on the job had begun several years before. It had started with Linsay Rousseau Burnett, a journalism graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley who had taken an internship at a national television network in the summer of 2009. She had been tasked with reporting on child farm labor, and it was on a trip to rural North Carolina that she discovered another story that urgently needed telling.

During a visit to a migrant farmworker community clinic, Rousseau Burnett met the outreach coordinator, who told the journalism student her own story. She had been smuggled from Mexico and brought to the United States to work in the fields. Her coyote was also the supervisor at the farm, and he had exploited his authority by raping her repeatedly. She had gotten pregnant by him eight times, and for years he had used threats and intimidation to keep her quiet. She told Rousseau Burnett she was not the only one.

It was a story almost too extreme to contemplate. When the television network declined to pursue it, one of Rousseau Burnett’s journalism school advisors, the veteran investigative reporter Lowell Bergman, encouraged her to continue working on the story once she returned to the university. Back in California, Rousseau Burnett dug into the topic and found that it was a systemic issue. “It came about by hearing one person’s story in North Carolina,” Rousseau Burnett says. “And we kept asking the question and we kept hearing from other people that this was a problem.”

As I would soon find out, this was a hard story to tackle. After years of reporting, Rousseau Burnett graduated to pursue jobs in journalism and eventually acting. Before she left the university, she gave her status updates and drafts to Bergman, who runs the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley. Another journalism student named Rosa Ramírez picked up the reporting for a time, but she, too, graduated before the project could be completed.

It was a story that Bergman continued to believe was worth telling, and it was a topic that he knew few media organizations would take on. He decided to assemble a team and find the funding to see the project through.

In 2012, as a journalist with The Center for Investigative Reporting, I was given the opportunity to join that reporting team, which was made up of journalists at UC Berkeley’s Investigative Reporting Program and at KQED-FM, the Northern California public radio station. The project, which we called “Rape in the Fields,” resulted in TV documentaries in English and Spanish for PBS Frontline and Univision, as well as bilingual public-radio pieces and newspaper articles.1

In more than a year of reporting, we found that, from the meatpacking plants of Iowa to the lettuce fields of California to the apple orchards of Washington, women expected to encounter sexual harassment, assault, and even rape at work.

As outsiders, we were shocked, but this was a problem that had been known within the farmworker community for generations. The confluence of economic precariousness, language barriers, shame, fear, and immigration status had created a workplace where women sexually abused believed they had no choice but to try to deflect or somehow endure the violence.

We studied the sexual harassment cases that the federal government had brought against agricultural employers since the late 1990s—a little more than forty lawsuits at the time—and we found that most cases involved multiple workers who had been sexually assaulted or raped by the same supervisors. Most involved claims of retaliation once the workers had worked up the nerve to complain. None of the civil cases had resulted in a criminal prosecution.

Even as we were in the process of seeking out the stories of farmworkers, we learned that this dynamic was not confined to America’s fields, orchards, and packing plants. In one of our first interviews on the farmworker project, we were told by William R. Tamayo, a government attorney, that the same problem existed in the janitorial industry.

That tip led to a follow-up piece, “Rape on the Night Shift,” in which the reporting team took a close look at an industry that operates in a largely underground or subcontracted fashion, where companies operate in obscurity and workers clean in anonymous buildings that government regulators and journalists rarely visit.2

Following eighteen months of reporting, we found that regardless of whether cleaners were hired by large companies or tiny, off-the-radar firms, the dynamics are similar to farm work. It is a job done by immigrants laboring in isolation for tiny paychecks, and if a supervisor decides to abuse their position, the combination of immigration status, financial constraints, and shame conspires to keep victims silent. We also found that some companies were dismissive of reports of sexual violence. In one case, the cleaning company told the offending supervisor to investigate himself. In another, the company ignored the eyewitness report of a church volunteer who said he’d seen a supervisor physically assault a female worker.

This book draws from that body of reporting from 2012 to 2015. I have also expanded on it by updating various case studies, and exploring how the same unfortunate pattern plays out among domestic workers, those who cook, clean, and care for families behind the locked doors of private homes. Their vulnerability to sexual violence echoed what we had heard from farmworkers and janitors. In their isolated workplaces, it was frequently their direct employers who groped them or propositioned them for sex. Domestic workers also face a unique legal hurdle: Because they have been purposely excluded from various federal labor laws, there is not always a clear path to recourse for workplace abuses such as sexual harassment and assault.

After looking at various industries that hire the most vulnerable workers, I’ve been forced to conclude that low-wage immigrants laboring in isolation are at unique risk of sexual assault and harassment. While it is not possible to know how often these abuses happen, they are not anomalies. The federal government estimates that about fifty workers are sexually assaulted each day, and in the industries that hire newcomers to the country in exchange for meager paychecks, such assault is a known and familiar workplace hazard.

As this book documents, however, there are few meaningful efforts to prevent workplace sexual violence before it starts. Instead, we unrealistically expect women with the most to lose to seek recourse by reporting the problem after the fact. The legal system—through filing a civil lawsuit or a criminal case—is often viewed as the clearest way to demand accountability. Workers can also go to their employers and unions to demand redress. Making a formal complaint helps emphasize that there can be consequences for this type of abusive conduct. But they are only part of the solution. These approaches are inherently reactive, and they require the confrontation of systemic roadblocks—such as deeply flawed notions of credibility—that create challenges to satisfying or just outcomes. They also do not, as esteemed law professor Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw has argued, consider the “intersectionality” of these workers’ experiences as women of color or immigrants, and how these identities impact the way they are perceived, how they might react, and the type of help they might need when faced with gender-based violence.3

Meanwhile, we know that prevention is possible. Decades of empirical research offers clear direction. While there are some heartening efforts to incorporate this research into worker training and advocacy programs, employers and policy makers have largely chosen not to use it.

In addition, advocates for female workers have for decades tried to make the case that sexual assault at work should not be dismissed and marginaliz

ed by employers and the government simply because it has historically been perceived as a “women’s issue.” Instead, they argue, gender-based violence should be viewed in the same way as other forms of on-the-job physical violence so that prevention plans are implemented, the government takes a proactive role in enforcement, and workers have an avenue for demanding accountability. Recently there have been successful efforts at the state level to recast this problem as an issue that can be averted through public policy. Employers may worry that these efforts are overly cumbersome, but this is the paradigm from which prevention can begin.

In the end, this book seeks to excavate and disrupt an unacceptable set of circumstances that promote silence. Whether victims of sexual violence choose to share their stories publicly or not is a deeply personal question, and there should never be a mandate that they do. By recounting the experiences of the immigrant women who have taken the improbable step of reporting workplace sexual harassment and assault, I am asking why we give so little real help to those who courageously come forward?

It took seven months of reporting for “Rape in the Fields” before we met Maricruz Ladino. She had worked at a lettuce farm in Salinas, California, where her supervisor propositioned her and gave her unwanted massages. When she rebuffed him, he threatened her. “He told me to keep in mind that he had the power to decide how much longer I could work there,” she recalls. “I was a single mother and I was scared. I was worried that if I didn’t do what he wanted me to do, I would lose my job, the source of income for my daughters and my mother, who was already alone.”

Then one day in 2006, Ladino’s supervisor told her he wanted her to come with him to check the crops in a remote field. That’s where he raped her. For years, she never told anyone about what had happened, but she began to find solace in writing letters to her deceased father in her journal. Through these epistolary conversations, Ladino realized that her father had taught her not to stand for the kind of injustice that had happened to her—either for herself or for others.

In a Day's Work

In a Day's Work